Liberating Pitch and Taming MIDI in Composer's Sketchpad

Mar 24, 2016 programming

This blog post is part of a series on the development of Composer's Sketchpad, a new iPad app for making musical rough drafts and doodles.

I wanted Composer’s Sketchpad to have the ability to represent musical notes at any pitch. In order to do this, I needed to solve two problems: representing arbitrary pitches internally and making them compatible with MIDI.

Human perception of pitch follows a logarithmic curve, meaning that a frequency will sound an octave higher when multiplied by two. However, we tend to think of notes in a linear fashion: C4 is a fixed distance from C3 on the piano, just as C3 is from C2.

The naive approach to representing pitch would be to simply store the frequency in hertz and be done with it. But this didn’t sit right with me: since my canvas depicted pitches linearly like on a piano keyboard, I’d have to be constantly taking the logarithm of my points and subsequently introducing possible floating point errors as we went up the ladder. The pitches would also have to be stored as irrational floating point numbers, making it impossible to tell whether a point is sitting precisely on a pitch gridline.

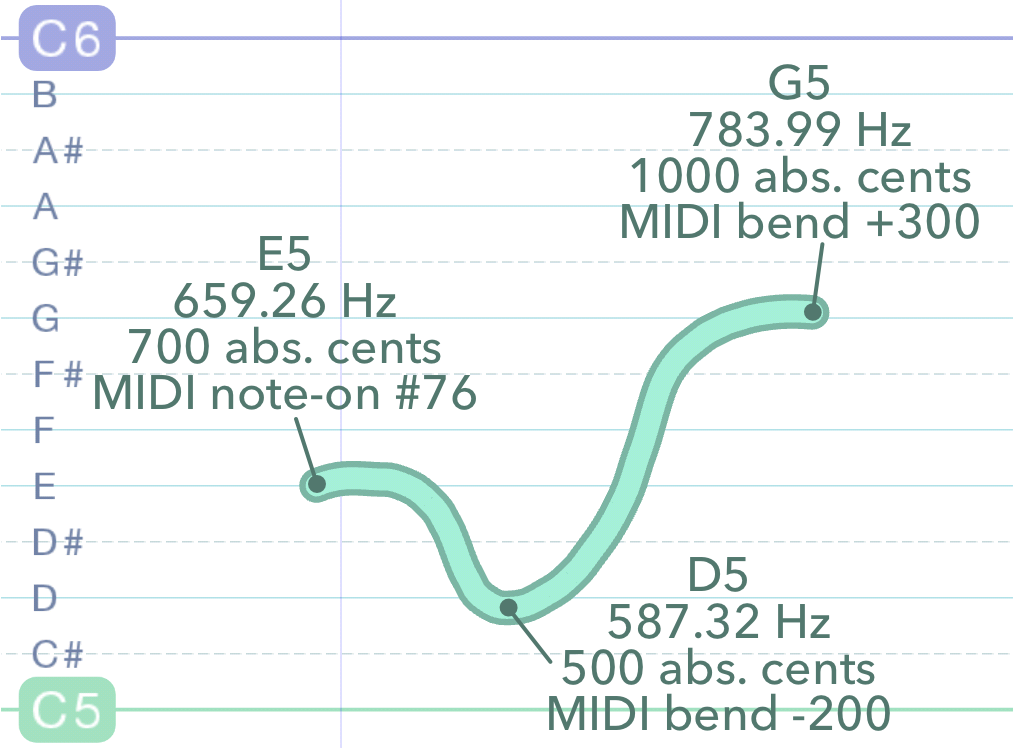

So I decided to represent my pitches as cents. Cents are the linear unit counterpart to frequency: C4 is 1200 cents from C3, and C3 is 1200 cents from C2. (Per equal temperament tuning, each piano key is 100 cents apart from the next.) This means that cents aren’t an absolute unit like pitch, but rather the function of two frequencies: in order to get the expected 1200 cents from C4 (261.6Hz) to C3 (130.8Hz) we take the base-2 logarithm of C4 divided by C3 and multiply by 1200. As convenient as these units were, I still needed to represent my points in an absolute way, and so I created an internal unit of “absolute cents”: simply the number of cents a pitch is from A440. If you peek inside a Composer’s Sketchpad JSON file, you’ll see that C4 has a value of -900, B4 a value of -1000, etc. Mathemtacially convenient and human-readable!

Different representations of pitch for the inflection points on a single note.

The second problem was a little trickier. Internally, the app was using the built-in MIDI functionality found on iOS, in the form of MusicPlayer and AUMIDISynth. Unfortunately, traditional MIDI — having been designed in the stone age of computing — didn’t support arbitrary pitch values. Instead, you were given a measly 128 MIDI notes, each corresponding to a note on a standard, equally-tempered (and slightly extended) piano. This was great for interfacing with hardware MIDI keyboards, but hardly appropriate for playing back arbitrary pitches.

(To be clear: MIDI is simply a standard for sending instructions to a synthesizer. While the standard is very limited and fiddly, it does have the advantage of being supported ubiquitously. You can also save your MIDI packets to a file and use it with a wide variety of software. However, synthesizers themselves are usually much more robust. When interfacing with them directly, you may well be able to play arbitrary pitches and use other custom functionality. The thing you’d lose by going this route is compatibility with existing technology, which is frankly a very big hurdle.)

There are several ways to alter the pitch of a MIDI note, some more widely supported than others. The most common is using the pitch-bend wheel. Another is using the MIDI Tuning “Standard” (which is in fact hardly supported anywhere). Yet another is using polyphonic aftertouch, but only after setting up your synthesizer to correctly parse the signals. For its ubiquity and semantic correctness, I decided to go with the pitch-bending approach. To play back an arbitrary pitch, I’d simply play the closest MIDI note and then bend it up or down to the desired frequency. However, there were two issues with this approach. First, the pitch-bend wheel applied bending to the entire keyboard range, not just individual notes. This meant that with the naive implementation, you could only play a single arbitrary pitch at a time! Second, the default range for the entire pitch-bend wheel was a measly whole tone up or down, which was simply insufficient for arbitrary bends. (For wider bends, one might consider getting around this problem by bending to a note, stopping the first note, playing the second note, and continuing the bend. However, this sounds pretty poor due to the fact that most instruments have a distinctive-sounding “attack” that appears as soon as you play a note. This makes the bend sound discontinuous at MIDI note boundaries.)

I’ll get into the specifics of my MIDI architecture in a later article, but in brief, I solved the first problem using MIDI channels and multiple MIDI instruments. A MIDI instrument can often have 16 so-called channels, which are sort of like presets. Each channel has its own setting for instrument, volume, vibrato, and — conveniently — pitch bend, among many other properties. Whenever you play a MIDI note, you assign it to a channel and it plays with the corresponding properties for that channel. For my use case, this meant that if I used each MIDI channel for playing just a single note at a time (as opposed to the usual approach of playing multiple notes per channel and assigning each channel to a unique instrument), I could have 16 notes simultaneously pitch-bending at once! I wanted more polyphonic notes than that, however, so I decided to simply create a new virtual MIDI synth for each instrumental layer in my app: 16 channels per instrument, with 10 maximum instruments at once (for now). Surprisingly, even 10 maxed-out MIDI synths playing simultaneously didn’t peg my iPad 3’s CPU too hard. Kudos to a great audio architecture!

The second problem — limited pitch-bend range — was solved using a so-called MIDI RPN, or registered parameter number. These are special, widely-supported MIDI commands that let you configure certain properties of your synth, with one of the primary ones being the range of your pitch-bend wheel. (Note that I say widely supported, not universally. Only about half the software I’ve tried seems to understand the pitch-bend range RPN. Fortunately, Apple’s built-in synth does just fine.) Rather than having each tick on my virtual pitch-bend wheel correspond to 0.024 cents (as is the default), I sent an RPN command at the start of playback to make each tick equal to one cent. Completely impractical for a physical weel, but quite conveinent for our use case! (Incidentally, this makes the new pitch-bend range +/- almost 7 octaves. Except for the most esoteric use cases, it’s totally unnecessary to go any further than that, since even a pitch-bend of a single octave sounds pretty terrible on most synths.)

All in all, it’s a messy, imperfect system, but it gets the job done. I can take a bunch of pitches stored as “absolute cents” in my JSON file, push them through a few conversion functions, retrieve a set of MIDI packets on the other end, send them to a bunch of virtual MIDI synths, and have them sound as the correct, precise audio frequencies through my speakers. Maybe someday a more modern standard like OSC will reign supreme and allow this sort of architecture to be radically simplified, but for now, we’re unfortunately a bit stuck in the 80’s.

—Archagon

March 24, 2016